On Sunday, February 1, 2009, I took part in my very first cadaver dissection lab. There were twenty-five students, three enthusiastic teachers, and five complacent cadavers. I didn’t pass out. I didn’t puke. As if I was at my studio, I donned my safety goggles, rubber gloves, old clothes, and a dust mask. And I dove right in.

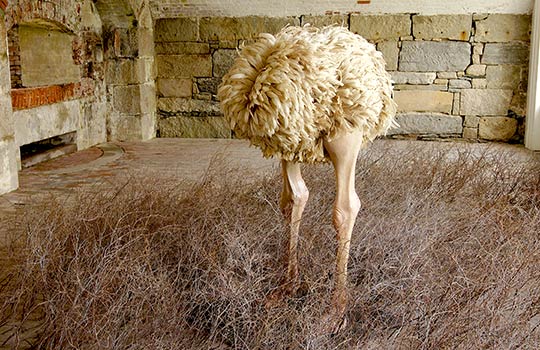

As a licensed massage therapist, I’ve probably given a couple thousand massages since graduating massage school in 2007 – and I’m just starting to understand the body on a level I’d previously glossed over in my work. We may be born with physical strengths or defects, but our actions, habits, thoughts, and feelings literally sculpt our appearance from birth to death. The body is a cherished puppet animated by our invisible selves. When we leave the body, we shed it like snake skin, wriggling out into the airy light, looking forward to the next incarnation.

A surgeon can open the abdomen and reach deep inside. Will he find a soul? He’ll chase it forever behind the folds of intestine and fat. He’ll arrive at the muscles of the back; he’ll reach right through to the other side, but the coquettish soul will not be captured. Sew the belly back up, and the person lives, is animated, makes supper, goes to the bathroom. Where was the soul hiding when the body lay gravely open like a cookbook on a kitchen table?

We revel in the flesh – we idolize, fetishize, medicate, and deprecate it. In my twenties, I thought my work was all about “The Body;” the flesh and the goo of it. In truth, it was about the experience of inhabiting a body: the poignant impossibility of comprehending one’s place in the cosmos from inside an imperfect cave of flesh. We are isolated within this body. But we love it that way. We’re dying to share this bodily experience with another, but we’ll never be able to consummate that idea completely. So we eat a bag of potato chips and call it a night.

Well, at least that’s what I do.